Enter if you Dare!

A late October walk on a sunny day – starting at Dupont station which is just north of Bloor on Line 1 (That’s the University side of the Yonge-University Line for those of you who, like me, haven’t mastered the TTC numbering system yet!). We walked a few blocks on Dupont before going under the railway tracks to Bridgman, then took a quick turn on Albany to get to Davenport. A short block later we were on Bathurst. Vaughan Road veers left off Bathurst just south of Bloor. We meandered a bit north of Bloor before walking back to St. Clair West station.

below: A bright and sparkly flower blooms on the southbound platform of Dupont subway station. This is one of the mosaics designed by James Sutherland in the series “Spadina Summer Under all Seasons” found around the station.

below: More Dupont station flowers to greet subway travelers, this time on the concourse level.

below: Taking the escalator up inside the dome at street level.

below: There is a Nick Sweetman mural of birds that wraps around the curve of a bench.

below: The curve matches that of the domed entrance to the station on the southeast corner of Dupont and Spadina.

below: Casa Loma in the distance, on the hill beyond the tracks. This is the view on Spadina north of Dupont.

below: Northeast corner of Dupont and Spadina

below: Big rounded arches, rooftop terraces in the back, and two turrets, all at the corner of St. George Street and Dupont.

below: Looking north on St. George, towards Dupont, 1904. Working on the street. The house with the two turrets is already there. The duplex on Dupont at the top of the street still exists too.

below: The duplex (176-178 Dupont) is difficult to see because like so many other older residences on main streets, an addition has been added to the front to facilitate a store or a restaurant. At the moment, 176 Dupont is a Mexican restaurant, even though the says Pastrami (close enough!).

below: Bruno Men’s Hairsylist and his quaint little sign.

below: On Dupont, east of Spadina is this mural by Catherine Cachia

below: Cozy and euphoric.

below: Bete Suk, Ethiopian Coffee shop

below: Northwest corner of Dupont and Spadina, and another domed subway entrance.

below: Looking west on Dupont

below: Another, much clearer, example of the transition of houses to businesses by building additions in front, are these two – Krispy Kreme and the faded Modern Laundry & Dry Cleaners.

below: West of Dupont, there are still some garages covered in street art.

below: This is 390 Dupont Street, part of which is now a coffee shop/vintage clothing store. I am not sure what the history of the building is but when I tried to research it, I discovered that there is a condo development being proposed for the site.

below: This is the neighbouring property, 388 Dupont. Two years ago when I walked this stretch, there was a blue and white development notice sign in front of the building (Dupont Street Scenes). When the application for redevelopment was first filed (2020), it was for an 11 storey building involving 374 to 388 Dupont. By 2023 the plan had evolved to 12 storeys and now included 390 Dupont as well. Because the site is adjacent to the CP Railway corridor, a train safety derailment wall along the entire back wall is part of the plan.

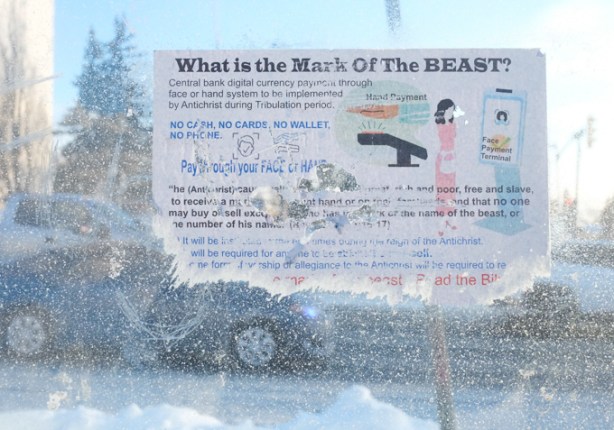

below: Although there is no posted notice of planning applications for this building, it appears to be empty. The front door is boarded up and there is a No Trespassing sign in the window.

below: Two years ago this building was in the early stages of construction.

below: Another theme that occurs over and over again on the streets of Toronto – the jumble of different eras. Very old brick houses and new glass and steel towers mixed together along with ages in between. The smaller older structures dwarfed by the newer ones that tower over them.

below: The Troy Lovegates mural of 10 faces on Howland & Dupont is still there and still looking vibrant. If you are interested, there are more images of this mural elsewhere in this blog.

below: Running parallel to the railway tracks, and just north of them.

below: The north side of the CP Railway corridor shows signs of its more industrial past. This building with its curved glass sidelights and other small Art Deco finishes, sits empty. Previously it was home to a plumbing company but they have moved to new quarters elsewhere in the city.

below: Tarragon Village mural by Elicser Elliott

below: There is also this mural, just around the corner on Albany, “You are not alone”. It was painted by Julia Prajza and Bareket (bkez). ‘You Are Not Alone Murals’ is a public mural project with over 100 murals completed. Their goal is to “inspire artists to create murals in their communities–sparking hope, connection, and conversations about mental health.” (quote taken from their website, youarenotalonemurals.com).

below: An intriguing series of photos in the windows… but I couldn’t get a closer look at them.

below: A large red heart and an even larger blue spruce tree.

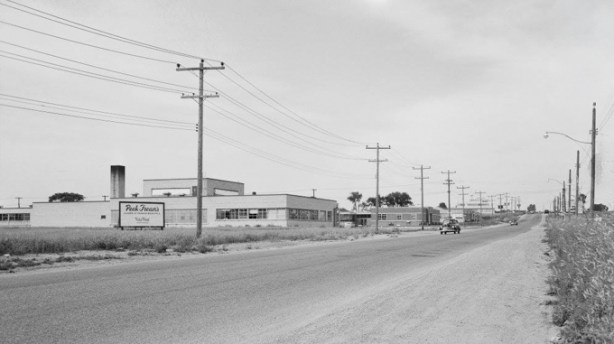

;

;

below: The paintings along the concrete wall on the west side of Bathurst have all been defaced.

below: Another touch of Art Deco in the neighbourhood

below: Bathurst Street houses

below: Playing in the playground

below: Store fronts on Bathurst

below: Looking north up Bathurst where Vaughan Road exits left. Vaughan Road was built in the 1920’s along an older trail that follows a now underground creek. From here, it runs more or less diagonally north and west to its northern end at Dufferin and Eglinton.

below: Choice laundry in the old brick building, on Vaughan Road.

below: Also on Vaughan Road, Zoomiez Doggie Daycare and Vaughan Road Pharmacy.

below: We met a couple of strangers. They weren’t very talkative though so we kept walking….

below: The gateposts on Strathearn Road mark the entrance to the former village of Forest Hill. Forest Hill was incorporated as a village in 1923 and then annexed by the City of Toronto in 1967.

below: There is a metal plaque at each end of the Glen Cedar pedestrian bridge over the Cedarvale Ravine. This is the one at the south end. The text is taken from the lyrics of “Anthem”, a song by Leonard Cohen. The first bridge here was built by Henry Pellatt (the same man responsible for Casa Loma) in 1912. It became a pedestrian bridge when it was modernized in 1989.

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your prefect offering.

There is a crack,

a crack in everything

it’s how the light get’s in

[and yes, the plaque has an apostrophe in gets]

below: Home is where our story begins.

below: At Bathurst and St. Clair – Da Best Pilipino Bakery and Deli

below: Waiting to cross Bathurst Street

below: Looking east on the north side of St. Clair, from Bathurst. St. Clair West subway station is just a few meters away.

below: There was once a gas station on the northeast corner of Bathurst and St. Clair West. Now it is a vacant lot with a few alien creatures like this one lurking about.

below: Happy Hallowe’en pumpkins! The frog’s not so certain though.

With thanks to Nancy who walked with me that day.